Intro

Despite Scala 3 officially launching back in 2021, it still manages to surprise — especially once you start poking around in the compiler’s darker corners.

Not long ago, while hacking on macros, I ran into a deceptively simple question:

Is it possible to write code that works with any type — regardless of its shape?

Not just Int or String. Not even just List[A] or Either[A, B]. But types that are functions over types. Unapplied type constructors. Type lambdas. Things with an unknown number of type parameters.

In practice, most logic involving type analysis — macros, reflection, automatic derivation — assumes you are working with fully applied types. If a type takes parameters, they are usually known and neatly “closed”.

But what if they aren’t?

What if a user of your library shows up with a type you never anticipated? One with two parameters. With five. With a type lambda. With a partially applied constructor. With something that doesn’t even have a name yet.

Sure, you can try to prepare separate code paths:

for one type parameter,

for two,

for three,

and so on…

Until your library starts looking more like a bug generator than an API.

That approach doesn’t scale.

It’s fighting a hydra with if-else.

And this is exactly where AnyKind enters the stage.

In this article, we’ll look at:

- where this type fits into Scala’s hierarchy,

- what problem it actually solves,

- and just as importantly — what it does not solve.

All examples were written using Scala 3.7.4, the latest version available at the time of writing.

The Any* Family

Before we talk about AnyKind, we need to rewind a bit and look at the world as Scala already sees it. Scala has always been very precise about one thing: values.

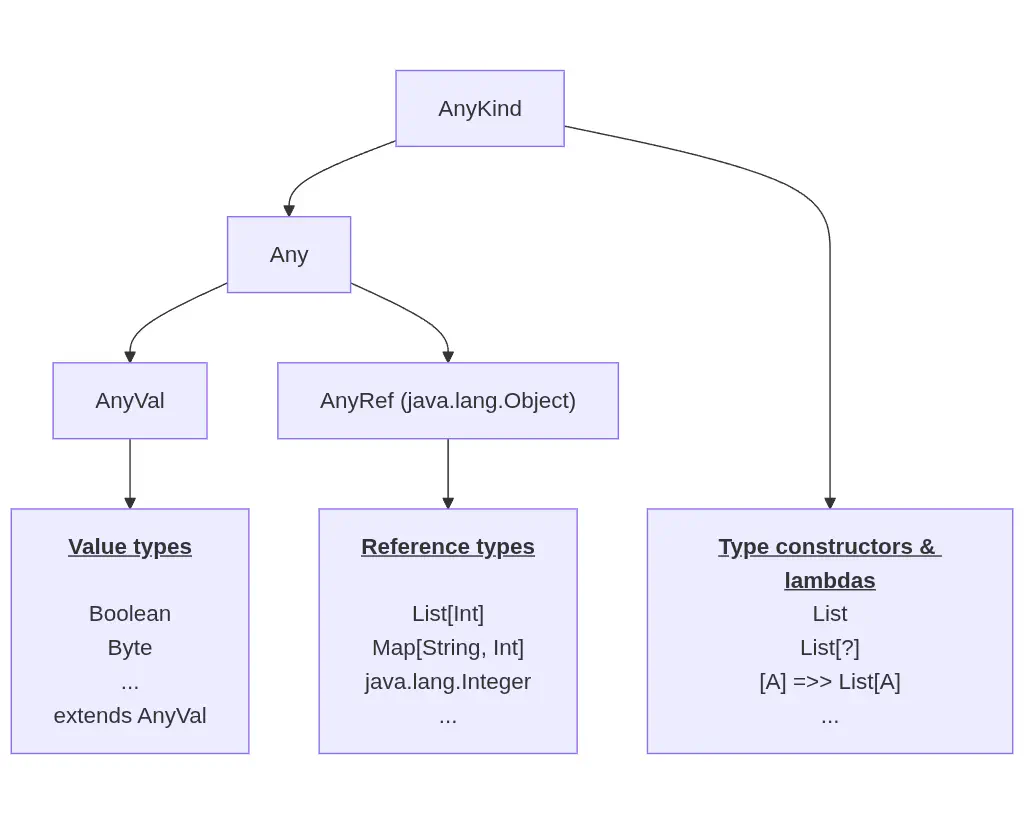

The entire hierarchy of Any, AnyVal, and AnyRef exists primarily to describe runtime objects — not abstractions, not type constructors, not type lambdas — just things that actually exist when your program runs.

Let’s start from the top.

Any

Any is the root of Scala’s value universe. If something exists at runtime — an Int, a String, a case class, an anonymous function — then, one way or another, it inherits from Any.

That makes Any the common ancestor of all values. So far, nothing surprising.

AnyVal

AnyVal separates value types from everything else. This includes all the primitives you already know:

- Boolean

- Byte

- Short

- Int

- Long

- Float

- Double

- Char

- Unit

These are the types that live closest to the metal. No object identity. No references. No heap allocation. At least in theory — the JVM still finds creative ways around this.

Scala also allows you to define your own value classes by extending AnyVal, mostly for performance and additional type safety. But the key thing here is:

AnyVal describes how values are represented at runtime.

Not how types behave. Not how type-level code works. Just memory and mechanics.

AnyRef

AnyRef is the other half of the universe. Everything that is not a value type ends up here:

- List

- Map

- Future

- Option

- java.lang.Integer

- Every class you’ve ever written

Under the hood, AnyRef is just Scala’s name for java.lang.Object. There’s even a proof:

| |

Extending AnyRef does not unlock any secret abilities.

The Missing Puzzle Piece

Up to this point, Scala has done an excellent job modeling values. But here’s the uncomfortable question: where do type constructors and type lambdas live?

They are not values. They never exist at runtime. They are not AnyVal. They are not AnyRef. And they don’t fit under Any, because it is a type of values, not a type of types.

Scala had a perfect taxonomy for objects. And almost no language at all to describe the shape of types. This wasn’t a big deal… Until people started doing serious type-level programming. And that’s exactly where AnyKind finally enters the picture.

Note: This is a conceptual view — values live under Any, while type shapes live under AnyKind.

Type Lambdas

Type lambdas don’t belong to the everyday toolbox of most programming languages. They usually show up only in languages with a strong functional bias or a particularly expressive type system. Scala happens to have both.

Ignoring theory for a moment, the best mental model is simple: a type lambda is just a function — but defined at the type level. Its arguments are types. And its result is also a type.

Life Before Scala 3

It may look like type lambdas arrived in Scala only with version 3. In reality, Scala 2 already had a rather… inventive workaround. Consider this example:

| |

What’s happening here is pure type-system gymnastics.

We define a refinement type that introduces a type member F, then use a type projection (#F) to extract it.

That F behaves like a type-level function — not because the syntax says so, but because the compiler allows it.

It just works.

Shiny New Syntax

Scala 3 replaces that trick with an official syntax:

| |

The shape is familiar — it looks like a lambda. There are just two small differences:

=>>instead of=>- this one lives entirely at the type level

And that subtle difference is everything.

They Are Not Values

A type lambda is not something you can hold in your hand. You cannot:

- create an instance of it

- store it in a variable

- pass it around at runtime

Before you do anything useful with it, you must apply it. And until you do — it’s not a concrete type. For example:

| |

This is just currying — but for types.

More Than One Parameter

Type lambdas aren’t limited to a single argument:

| |

Here Apply is a type-level function that takes:

- a HKT

F - a type

A

And applies one to the other. It’s higher-order programming. Just… without values.

AnyKind

After Any, AnyVal, and AnyRef, Scala 3 finally adds the missing puzzle piece: AnyKind. This is the type that was never really there before — a name for “any shape of type”. Not just values. Not just applied types. But also: constructors, higher-kinded types, and type lambdas.

The promise is simple: take any type — no matter what its shape is — and you can pass it here. And indeed, AnyKind is defined as the supertype of all types, regardless of their kind. Which sounds powerful. Almost suspiciously powerful. So let’s test that promise.

The Good News

In practice, AnyKind really does what it claims. You can feed it:

- plain types like Any or Nothing

- higher-kinded types like List or Map

- fully applied ones like List[Int]

- type lambdas

- even type constructors that take other constructors

Everything fits. For the first time in Scala, we get a single abstraction that is able to accept a type of any shape. Not “any value-level type”. Not “any type constructor with one parameter”. Not “any binary type”. Literally: any kind of type.

So did we just unlock god mode?

The Catch

Not even close.

A <: AnyKind tells us one thing: this is some type.

And absolutely nothing else. It doesn’t tell us:

- whether it’s a normal type

- or a unary constructor

- or a type lambda

- or something that takes three parameters and feels personally offended when you get two wrong

We don’t know its kind. And without knowing the kind, the compiler can’t safely let us do anything meaningful. This is where you start seeing errors like:

Missing type parameters for A

Because from the compiler’s point of view, A could be:

IntList[X] =>> XMap[?, ?]F[_] =>> G[_] =>> F[G]

And without narrowing it down, none of these operations are guaranteed to make sense:

- creating a value of

A - treating

Aas a normal type - blindly applying type arguments

- assuming it even has parameters at all

AnyKind doesn’t give you power. It gives you access.

The Real Meaning of AnyKind

This is the key mental shift. AnyKind is not more than Any. It’s orthogonal to Any. Any classifies values. AnyKind classifies shapes of types.

It is not a runtime abstraction.

It is not a data model.

It is not something you ever hold in a variable.

It is a compile-time concept.

Where Things Get Interesting

Accepting a type of any shape is only step one. The real work starts when you ask:

“Okay… but what kind of type is this actually?”

Unary?

Binary?

Value-level?

Type-level function?

And answering that question is not something AnyKind itself can do for you. This is where we leave the world of declarations and enter the world of inspection. Which basically means macros. Because if AnyKind gives you a black box, macros are how you open it.

Handling AnyKind with Macros

So far, AnyKind only let us accept types of any shape.

Now comes the harder part: actually understanding what kind of type we’re dealing with.

When A <: AnyKind lands in a macro, the compiler gives us exactly one piece of information: this is some type.

And that’s it.

Before we can transform it, normalize it, or derive anything from it — we first have to recognize its shape. In practice, every macro that works with AnyKind ends up classifying the input into a small number of structural categories. Most real-world cases fall into one of these four:

- Type lambda — a type-level function like

[A] =>> A - Type constructor — an unapplied type such as

ListorMap - Type with wildcards — partially applied forms like

List[?]orMap[?, ?] - Concrete type — a fully applied, value-level type such as

IntorList[Int]

These shapes are not interchangeable. Each one:

- behaves differently,

- accepts different operations,

- and must be handled explicitly in macro logic.

The rest of this section shows two concrete macro patterns. First, how to recognize the shape of a type. And then, how to transform it into something easier to work with. The goal here is not to explain macro internals or the Scala reflection API. This is just a high-level demonstration of what becomes possible once you start treating types as data.

Example 1 — Determining the Arity of a Type

The following macro determines the arity of a type. That is, how many type parameters it expects before it becomes concrete. This example is not about how the macro is implemented, But about the kind of information that becomes accessible once AnyKind enters the picture.

| |

Below you can see the results of running this macro on a few example types:

| |

Example 2 — Transforming a Type into Curried Form

This example takes things one step further. Instead of merely recognizing the shape of a type, we reshape it. The following macro transforms a type into its curried form, regardless of how it was originally declared.

| |

Below you can see the results of running this macro on a few example types:

| |

Conclusion

AnyKind is not “a better Any”. It doesn’t add power at runtime, and it doesn’t make the type system simpler. What it does is introduce a missing concept — a way to talk about the shape of types.

By itself, AnyKind only opens the door. Macros are what make it useful. They let you inspect and transform types once their shape becomes visible.

Together, they move Scala toward one idea: types are not just labels — they are data.

Further Reading

In case you enjoyed this article, here are a few more you might find useful: